When men stop shaving, others start talking. Across the past two centuries journalists, preachers, physicians, and social-media influencers, have treated facial hair as a barometer for health, morality and status. The mid-Victorian notion that whiskers could fend off tuberculosis has given way to twenty-first-century debates about bacterial shedding in hospital theaters and respirator leaks during pandemics. Meanwhile a booming beard-care market, worth well over one billion US dollars in 2025, shows that ideology is still entwined with commerce. Understanding why the beard keeps swinging between celebration and suspicion offers a window onto changing anxieties about the body, technology, and identity.

Victorian Britain and the sudden cult of whiskers : In 1847 the pamphleteer William Henry Henslowe attacked the “fatal fashion” of daily shaving, claiming it weakened men and undermined Christian virtue. His tract was only the loudest in a flurry of mid-century publications that framed the beard as both a God-given ornament and a hygienic necessity. Letter-writers to The Times argued that a moustache filtered coal smoke, and Edwin Creer’s Popular Treatise on the Hair insisted that shaving made clerks vulnerable to bronchitis. By the early 1860s the imagery had flipped: portraits of statesmen such as William Gladstone featured luxuriant “Dundreary” side-whiskers that signified sober masculinity. The speed of the shift illustrates how quickly medical folklore can reshape fashion when it resonates with social fears about urban disease and moral decline.

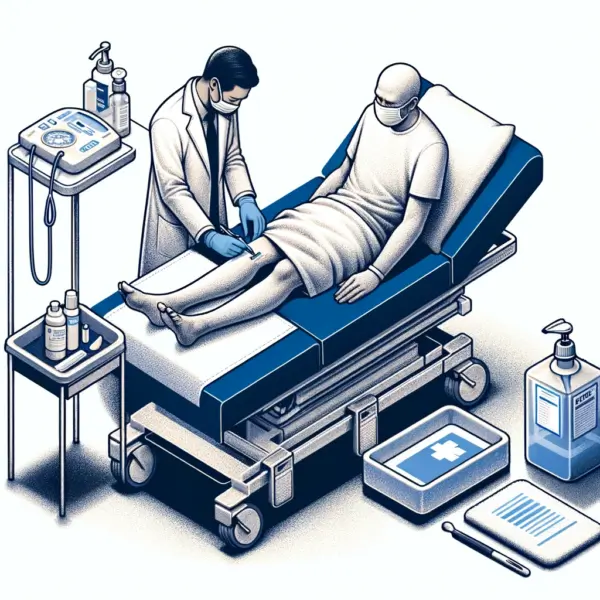

Health claims and what modern science now shows : Victorian hygienists could not have known about microbes, but their instinct that beards interact with the environment was partly correct. A 2012 dosimetric study showed that beards can block up to one-third of erythema-inducing ultraviolet radiation, providing the equivalent of a sun-protection factor between roughly 2 and 21 depending on hair density and solar angle. More recently a 2025 review of operating-theatre studies found conflicting but broadly reassuring evidence that surgeons with covered beards do not cause higher rates of surgical-site infection provided they follow the same scrub protocol as their clean-shaven colleagues. In community settings the picture is equally nuanced. One 2022 investigation of hospital staff swabbed bearded and non-bearded workers and detected slightly higher rates of bacterial shedding when beards were rubbed, but no consistent difference in pathogenic colonisation on the skin itself. The emerging consensus is that washing frequency, not shaving, is the decisive variable.

Religious symbolism beyond the West : The Victorian debate drew heavily on the book of Genesis and Anglo-Saxon myth, but globally the beard has long served as a marker of faith. For many Sikhs kesh, the uncut hair of body and head, is a mandatory article of faith signifying spiritual discipline; campaigns against turbans and beards in colonial and post-9/11 contexts therefore strike directly at communal identity. In Muslim jurisprudence, classical hadith urge men to “trim the moustache and let the beard grow,” and contemporary scholarship interprets the practice as a visible sign of adherence to the sunnah and resistance to homogenising secular culture. These traditions remind us that disputes over facial hair are never merely cosmetic: they can touch on questions of conscience, racial profiling and legal rights in workplaces from the US Air Force to Indian schools.

The twentieth-century swing to the clean shave : The First World War ushered in fifty years of near-universal smooth chins. Militaries required recruits to shave so that early gas masks could form an airtight seal, and the norm persisted because of changing technology at home. King C. Gillette’s disposable-blade safety razor, patented in 1901, made a daily shave quick and affordable, turning a pre-industrial luxury into a modern routine. Adverts equated a clean face with professionalism and patriotic hygiene, amplifying post-war anxieties about infectious disease and industrial discipline. Changing idealised images of masculinity also overlapped with new roles for consumer goods: by mid-century the bearded man was more likely to appear as a villain in a Hollywood western movie than as a statesman.

Counter-culture, civil rights and the slow revival : Everything changed again in the 1960s. Civil-rights leaders such as Malcolm X wore neat goatees that subverted corporate norms, while anti-war protestors and folk musicians grew unruly “freedom beards.” By the 1970s musicians from country to disco reclaimed full whiskers as symbols of authenticity. Cultural historians argue that each swing of the pendulum typically follows a backlash against the aesthetic of the previous generation: if the Victorian beard reacted to Regency effeminacy, the hippie beard resisted mid-century conformity.

Pandemic masks and twenty-first-century workplace dilemmas : Facial hair again became a practical concern in 2020 during the first months of COVID-19. The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration issued emergency memoranda warning that certain respirators cannot seal over thick beards, urging employers either to switch to loose-fitting hoods or to reassign staff whose religious obligations prevent shaving. Similar conversations played out in UK National Health Service trusts and on social-media forums where Muslim and Sikh health-care workers shared tips for beard coverings. These events show how health crises can resurrect debates that had seemed settled for decades.

Charity campaigns and the rebranding of facial hair : Whiskers also re-entered mainstream offices through philanthropy. “Movember,” launched in Australia in 2003, encourages a month-long moustache to raise money for testicular- and prostate-cancer research; spinoffs such as “No-Shave November” have raised more than one million US dollars through partner campaigns like the 2024 Penn State Health drive alone. These initiatives normalise eccentric facial hair while framing it as altruistic, further blurring the line between grooming choice and moral virtue.

The grooming business and the green critique : Corporations have responded enthusiastically. Market analysts estimate that beard-oil sales will reach between 1.04 and 1.42 billion US dollars in 2025, with annual growth rates above seven per cent as premium organic formulations enter drugstore aisles. Add combs, balms and electrical trimmers and the wider beard-care segment already tops 3.4 billion US dollars. Yet the resurgence has also provoked an environmental reckoning. Eco-audits note that billions of disposable plastic razors still enter landfill each year, and their spring-steel blades make recycling difficult, strengthening the case for long-lasting safety razors or simply skipping the shave. Whether consumers grow beards out of fashion or environmental concern, the result is the same: a lucrative niche for personal-care brands.

Cosmetic surgery and the pursuit of thicker stubble : Some men now pay surgeons to achieve the look earlier generations tried to erase. Follicular-unit extraction for beard enhancement has become one of the fastest-growing categories of hair transplantation according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, mainly driven by patients in Asia and the Middle East who view dense stubble as a marker of masculinity. Although precise global figures are hard to verify, congress reports from 2023 describe waiting lists of several months at major centres in Istanbul and Mumbai.

Conclusion : From nineteenth-century tracts that blamed razors for tuberculosis to Instagram hashtags that showcase artisanal balm, the beard’s meaning has never stood still. Medical evidence now suggests that a well-washed beard is neither a significant health hazard nor a miracle filter; its risks and benefits depend on hygiene, environment and personal skin physiology. Commercially, facial hair sits at an intersection of religion, masculinity, philanthropy, and sustainability, its significance always available for reinvention. The next swing of the pendulum may be driven by climate pledges, by augmented-reality beauty filters, or by another pandemic, but one lesson from the last 200 years is clear: the politics of shaving are rarely just skin-deep.

Bibliography

11711645 {11711645:7Z83D5WM},{11711645:NCW8ZBB6},{11711645:55X3GE5X},{11711645:Q8P2HL6T},{11711645:D5K9ZPJ3},{11711645:MNWMGLFM},{11711645:CNER5CSN},{11711645:IFGM6HRS},{11711645:VRTAI4AX},{11711645:6I64QK98},{11711645:UENZPBP6} 1 vancouver 50 date asc 1920 https://www.keratin.com/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/ %7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3Afalse%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%22NCW8ZBB6%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BBeard%20Oil%20Market%20Size%2C%20Share%20%26amp%3B%20Growth%20Analysis%20Report%202030.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Beard%20Oil%20Market%20Size%2C%20Share%20%26%20Growth%20Analysis%20Report%202030%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20global%20beard%20oil%20market%20size%20was%20valued%20at%20USD%20979.6%20million%20in%202024%20and%20is%20expected%20to%20expand%20at%20a%20CAGR%20of%207.4%25%20from%202025%20to%202030%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A31%3A41Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%227Z83D5WM%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BPenn%20State%20Health%2C%20Mid%20Penn%20Bank%20raise%20%24340%2C000%20during%20ninth%20%26%23x2018%3BNo%20Shave%20November%26%23x2019%3B%20%7C%20Penn%20State%20University.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Penn%20State%20Health%2C%20Mid%20Penn%20Bank%20raise%20%24340%2C000%20during%20ninth%20%5Cu2018No%20Shave%20November%5Cu2019%20%7C%20Penn%20State%20University%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Penn%20State%20Health%20and%20Mid%20Penn%20Bank%20raised%20%24340%2C000%20through%20their%20ninth%20consecutive%20%5Cu201cNo%20Shave%20November%5Cu201d%20campaign%2C%20officially%20crossing%20the%20%241%20million%20mark%20for%20funds%20raised%20since%20the%20launch%20of%20this%20annual%20initiative.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A31%3A45Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22D5K9ZPJ3%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Creer%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221865%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BCreer%20E.%20A%20Popular%20Treatise%20on%20the%20Human%20Hair%3A%20Its%20Management%2C%20Improvement%2C%20Presentation%2C%20Restoration%20and%20the%20Causes%20of%20Its%20Decay%2C%20with%20Some%20Observations%20on%20the%20Use%20of%20Powders%2C%20Face%20Paints%2C%20Cosmetics%2C%20and%20Hairdyes.%20The%20author%3B%201865.%20104%20p.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20Popular%20Treatise%20on%20the%20Human%20Hair%3A%20Its%20Management%2C%20Improvement%2C%20Presentation%2C%20Restoration%20and%20the%20Causes%20of%20Its%20Decay%2C%20with%20Some%20Observations%20on%20the%20Use%20of%20Powders%2C%20Face%20Paints%2C%20Cosmetics%2C%20and%20Hairdyes%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Edwin%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Creer%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221865%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A30%3A42Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22VRTAI4AX%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Parisi%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222012-07-01%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BParisi%20AV%2C%20Turnbull%20DJ%2C%20Downs%20N%2C%20Smith%20D.%20Dosimetric%20investigation%20of%20the%20solar%20erythemal%20UV%20radiation%20protection%20provided%20by%20beards%20and%20moustaches.%20Radiation%20Protection%20Dosimetry.%202012%20July%201%3B150%283%29%3A278%26%23x2013%3B82.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Dosimetric%20investigation%20of%20the%20solar%20erythemal%20UV%20radiation%20protection%20provided%20by%20beards%20and%20moustaches%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22A.%20V.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Parisi%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22D.%20J.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Turnbull%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22N.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Downs%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22D.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Smith%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222012-07-01%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1093%5C%2Frpd%5C%2Fncr418%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220144-8420%2C%201742-3406%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A21%3A51Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%226I64QK98%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Rana%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222019-10-12%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BRana%20M%2C%20Qin%20DB%2C%20Vital-Gonzalez%20C.%20Mistaken%20Identities%3A%20The%20Media%20and%20Parental%20Ethno-Religious%20Socialization%20in%20a%20Midwestern%20Sikh%20Community.%20Religions.%202019%20Oct%2012%3B10%2810%29%3A571.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Mistaken%20Identities%3A%20The%20Media%20and%20Parental%20Ethno-Religious%20Socialization%20in%20a%20Midwestern%20Sikh%20Community%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Meenal%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Rana%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Desiree%20B.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Qin%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Carmina%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Vital-Gonzalez%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Strong%20anti-Islamic%20sentiments%20increased%20dramatically%20after%20the%209%5C%2F11%20terror%20attacks%20on%20the%20United%20States%2C%20leading%20to%20an%20uptick%20in%20prejudice%20and%20the%20perpetration%20of%20hate%20crimes%20targeting%20Muslims.%20Sikh%20men%20and%20boys%2C%20often%20mistaken%20for%20Muslims%2C%20suffered%20as%20collateral%20damage.%20The%20overall%20health%20of%20both%20communities%20has%20been%20adversely%20affected%20by%20these%20experiences.%20Faced%20with%20such%20realities%2C%20communities%20and%20parents%20often%20adopt%20adaptive%20behaviors%20to%20foster%20healthy%20development%20in%20their%20children.%20In%20this%20paper%2C%20drawing%20on%20interviews%20with%2023%20Sikh%20parents%20from%2012%20families%2C%20we%20examine%20Sikh%20parents%5Cu2019%20ethno-religious%20socialization%20of%20their%20children.%20The%20confluence%20of%20media%20stereotyping%20and%20mistaken%20identities%20has%20shaped%20Sikh%20parents%5Cu2019%20beliefs%20regarding%20their%20children%5Cu2019s%20retention%5C%2Frelinquishment%20of%20outward%20identity%20markers.%20Sikh%20parents%2C%20in%20general%2C%20are%20concerned%20about%20the%20safety%20of%20their%20boys%2C%20due%20to%20the%20distinctive%20appearance%20of%20their%20religious%20markers%2C%20such%20as%20the%20turban.%20They%20are%20engaged%20in%20a%20constant%20struggle%20to%20ensure%20that%20their%20children%20are%20not%20identified%20as%20Muslims%20and%20to%20protect%20them%20from%20potential%20harm.%20In%20most%20of%20the%20families%20in%20our%20study%2C%20boys%20were%20raised%20to%20give%20up%20wearing%20the%20indicators%20of%20their%20ethno-religious%20group.%20In%20addition%2C%20many%20parents%20took%20responsibility%20for%20educating%20the%20wider%20community%20about%20their%20ethno-religious%20practices%20through%20direct%20communication%2C%20participation%20in%20cultural%20events%2C%20and%20support%20of%20other%20ethno-religious%20minorities.%20Policy%20implications%20are%20discussed.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222019-10-12%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.3390%5C%2Frel10100571%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%222077-1444%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A21%3A41Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%2255X3GE5X%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Withey%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222021-02-11%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BWithey%20A.%20Concerning%20Beards%3A%20Facial%20Hair%2C%20Health%20and%20Practice%20in%20England%201650-1900.%20Bloomsbury%20Academic%3B%202021.%20343%20p.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Concerning%20Beards%3A%20Facial%20Hair%2C%20Health%20and%20Practice%20in%20England%201650-1900%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Alun%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Withey%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22This%20book%20is%20open%20access%20and%20available%20on%20www.bloomsburycollections.com.Providing%20a%20new%20understanding%20of%20the%20meanings%20and%20motivations%20behind%20the%20wearing%20of%20beards%2C%20moustaches%20and%20whiskers%2C%20and%20their%20associated%20practices%20and%20practitioners%2C%20this%20book%20provides%20an%20important%20new%20long-term%20perspective%20on%20health%20and%20the%20male%20body%20in%20British%20society.%20It%20argues%20that%20the%20male%20face%20has%20long%20been%20an%20important%20site%20for%20the%20articulation%20of%20bodily%20health%20and%20vigour%2C%20as%20well%20as%20masculinity.Through%20an%20exploration%20of%20the%20history%20of%20male%20facial%20hair%20in%20England%2C%20Alun%20Withey%20underscores%20its%20complex%20meanings%2C%20medical%20implications%20and%20socio-cultural%20significance%20from%20the%20mid-17th%20to%20the%20early%2020th%20century.%20Herein%2C%20he%20charts%20the%20gradual%20shift%20in%20concepts%20of%20facial%20hair%20and%20shaving%20-%20away%20from%20%26%23039%3Bformal%26%23039%3B%20medicine%20and%20practice%20-%20towards%20new%20concepts%20of%20hygiene%20and%20personal%20grooming.This%20book%20is%20part%20of%20the%20Facialities%20series%2C%20which%20explores%20the%20social%2C%20cultural%20and%20political%20significance%20of%20the%20face%20in%20human%20history.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222021-02-11%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%229781350127845%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A31%3A18Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22CNER5CSN%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22El%20Edelbi%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222022-10-07%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BEl%20Edelbi%20M%2C%20Hassanieh%20J%2C%20Malaeb%20N%2C%20Abou%20Fayad%20A%2C%20Jaafar%20RF%2C%20Sleiman%20A%2C%20et%20al.%20Facial%20microbial%20flora%20in%20bearded%20versus%20nonbearded%20men%20in%20the%20operating%20room%20setting%3A%20A%20single-center%20cross-sectional%20STROBE-compliant%20observational%20study.%20Medicine%20%28Baltimore%29.%202022%20Oct%207%3B101%2840%29%3Ae29565.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Facial%20microbial%20flora%20in%20bearded%20versus%20nonbearded%20men%20in%20the%20operating%20room%20setting%3A%20A%20single-center%20cross-sectional%20STROBE-compliant%20observational%20study%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Mostapha%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22El%20Edelbi%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Joelle%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hassanieh%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Nancy%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Malaeb%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Antoine%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Abou%20Fayad%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Rola%20F.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Jaafar%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ahmad%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Sleiman%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Abdelkader%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Abedelrahim%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Zeina%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Kanafani%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ghassan%20M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Matar%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ahmad%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Zaghal%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Beards%20are%20controversial%20in%20the%20operating%20room%20setting%20because%20of%20the%20possible%20retention%20and%20shedding%20of%20pathogens.%20Surgical%20site%20infection%20poses%20a%20significant%20burden%20on%20healthcare%20systems.%20All%20male%20healthcare%20workers%20who%20entered%20the%20operating%20room%20were%20approached%20to%20participate%20in%20the%20study.%20Four%20facial%20swab%20samples%20were%20anonymously%20collected%20and%20a%20hygiene%20practice%20questionnaire%20was%20administered.%20Sample%20A%20was%20taken%20from%20the%20upper%20and%20lower%20lips%2C%20sample%20B%20from%20cheeks%2C%20and%20samples%20C%20and%20D%20were%20collected%20by%2020%20and%2040%5Cu2009cm%20shedding%20below%20the%20face.%20Colony-forming%20units%20%28CFUs%29%20and%20minimum%20inhibitory%20concentrations%20%28MICs%29%20of%20meropenem%20resistance%20were%20determined%20for%20samples%20A%20and%20B.%20Random%20samples%20from%20A%2C%20B%2C%20C%2C%20and%20D%2C%20in%20addition%20to%20meropenem-resistant%20isolates%20were%20cultured%20with%20chlorohexidine.%20Sixty-one%20bearded%20and%2019%20nonbearded%20healthcare%20workers%20participated%20in%20the%20study.%2098%25%20were%20positive%20for%20bacterial%20growth%20with%20CFU%20ranging%20between%2030%5Cu2009%5Cu00d7%5Cu2009104%20and%20200%5Cu2009%5Cu00d7%5Cu2009106%20CFU%5C%2FmL.%20Bacterial%20growth%20was%20significantly%20higher%20in%20bearded%20participants%20%28P%20%26lt%3B%20.05%29.%20Eighteen%20%2827.1%25%29%20isolates%20were%20resistant%20to%20meropenem%3B%20of%20these%20which%2014%20%2877.8%25%29%20were%20from%20bearded%20participants%2C%20this%20was%20not%20statistically%20significant.%20Chlorohexidine%20was%20effective%20in%20inhibiting%20the%20growth%20of%20all%20strains%20including%20the%20meropenem-resistant%20isolates.%20Bearded%20men%20in%20the%20operating%20room%20had%20a%20significantly%20higher%20facial%20bacterial%20load.%20Larger-scale%20resistance%20studies%20are%20needed%20to%20address%20facial%20bacterial%20resistance%20among%20healthcare%20workers%20in%20the%20operating%20room.%2C%20This%20study%20aimed%20to%20estimate%20the%20facial%20microbial%20load%20and%20identify%20strains%20and%20antimicrobial%20resistance%20profiles%20in%20bearded%20versus%20nonbearded%20male%20healthcare%20workers%20in%20the%20operating%20room%20of%20a%20tertiary%20hospital%20in%20the%20Middle%20East.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222022-10-07%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1097%5C%2FMD.0000000000029565%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220025-7974%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A23%3A40Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22MNWMGLFM%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Brewer%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222023-12-07%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BBrewer%20G%2C%20Singh%20J%2C%20Lyons%20M.%20The%20Lived%20Experience%20of%20Racism%20in%20the%20Sikh%20Community.%20J%20Interpers%20Violence.%202023%20Dec%207%3B39%2811%26%23x2013%3B12%29%3A2415%26%23x2013%3B36.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Lived%20Experience%20of%20Racism%20in%20the%20Sikh%20Community%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Gayle%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Brewer%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Jatinder%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Singh%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Minna%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Lyons%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20Sikh%20community%20may%20be%20more%20visible%20and%20vulnerable%20to%20racism%20than%20other%20religious%20groups%2C%20and%20previous%20research%20has%20documented%20the%20racism%20targeted%20at%20Sikh%20men%20and%20women%20in%20the%20United%20States.%20Relatively%20few%20studies%20have%2C%20however%2C%20addressed%20the%20racism%20experienced%20by%20Sikh%20communities%20in%20other%20countries%2C%20where%20racism%20may%20be%20less%20closely%20connected%20to%20the%20events%20of%209%5C%2F11.%20The%20present%20study%20investigates%20the%20lived%20experience%20of%20racism%20in%20Sikh%20adults%20living%20in%20the%20United%20Kingdom.%20Six%20participants%20%285%20male%2C%201%20female%29%20aged%2019%20to%2030%5Cu2009years%20%28M%5Cu2009%3D%5Cu200924.17%2C%20SD%5Cu2009%3D%5Cu20093.98%29%20were%20recruited%20via%20advertisements%20placed%20on%20social%20media.%20Both%20Amritdhari%20Sikhs%20%28n%5Cu2009%3D%5Cu20094%29%20who%20had%20undertaken%20the%20Amrit%20Sanskar%20initiation%20ceremony%20or%20commitment%20and%20Sahajdhari%20Sikhs%20%28n%5Cu2009%3D%5Cu20092%29%20who%20had%20not%20undertaken%20the%20initiation%20participated.%20Semi-structured%20interviews%20were%20conducted%20%28totaling%20372%5Cu2009minutes%20of%20interview%20data%29%2C%20covering%20a%20range%20of%20subjects%20including%20personal%20experiences%20of%20racism%20and%20subsequent%20responses%20to%20the%20racist%20abuse.%20Interpretative%20Phenomenological%20Analysis%20of%20the%20interview%20transcripts%20identified%20five%20superordinate%20themes.%20These%20were%20%281%29%20Appearance%20and%20Visibility%3B%20%282%29%20Inevitability%20and%20Normalization%3B%20%283%29%20Coping%20and%20Conformity%20%28Religion%20as%20Support%2C%20Fitting%20In%2C%20Internalization%29%3B%20%284%29%20Education%20and%20Understanding%3B%20and%20%285%29%20Bystander%20Behavior%20%28Experiences%20of%20Intervention%2C%20Religious%20Duty%20to%20Intervene%2C%20Consequences%20of%20Intervention%29.%20Findings%20highlight%20the%20extent%20to%20which%20racism%20occurs%20and%20the%20increased%20vulnerability%20of%20the%20Sikh%20community%20%28e.g.%2C%20appearance%20being%20the%20focus%20of%20racist%20abuse%29.%20Findings%20also%20highlight%20the%20importance%20of%20religion%20as%20a%20source%20of%20support%20and%20cultural%20pride%20and%20the%20significance%20of%20education%20and%20bystander%20behavior.%20Future%20research%20should%20further%20investigate%20these%20themes%20and%20introduce%20interventions%20to%20support%20the%20safety%20and%20well-being%20of%20members%20of%20the%20Sikh%20community%20experiencing%20racist%20abuse.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222023-12-7%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1177%5C%2F08862605231218225%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220886-2605%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A24%3A03Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22UENZPBP6%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Oldstone-Moore%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222024-05-31%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BOldstone-Moore%20C.%20Of%20Beards%20and%20Men%3A%20The%20Revealing%20History%20of%20Facial%20Hair.%20University%20of%20Chicago%20Press%3B%202024.%20347%20p.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Of%20Beards%20and%20Men%3A%20The%20Revealing%20History%20of%20Facial%20Hair%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Christopher%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Oldstone-Moore%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Beards%5Cu2014they%26%23039%3Bre%20all%20the%20rage%20these%20days.%20Take%20a%20look%20around%3A%20from%20hip%20urbanites%20to%20rustic%20outdoorsmen%2C%20well-groomed%20metrosexuals%20to%20post-season%20hockey%20players%2C%20facial%20hair%20is%20everywhere.%20The%20New%20York%20Times%20traces%20this%20hairy%20trend%20to%20Big%20Apple%20hipsters%20circa%202005%20and%20reports%20that%20today%20some%20New%20Yorkers%20pay%20thousands%20of%20dollars%20for%20facial%20hair%20transplants%20to%20disguise%20patchy%2C%20juvenile%20beards.%20And%20in%202014%2C%20blogger%20Nicki%20Daniels%20excoriated%20bearded%20hipsters%20for%20turning%20a%20symbol%20of%20manliness%20and%20power%20into%20a%20flimsy%20fashion%20statement.%20The%20beard%2C%20she%20said%2C%20has%20turned%20into%20the%20padded%20bra%20of%20masculinity.%20%20Of%20Beards%20and%20Men%20makes%20the%20case%20that%20today%26%23039%3Bs%20bearded%20renaissance%20is%20part%20of%20a%20centuries-long%20cycle%20in%20which%20facial%20hairstyles%20have%20varied%20in%20response%20to%20changing%20ideals%20of%20masculinity.%20Christopher%20Oldstone-Moore%20explains%20that%20the%20clean-shaven%20face%20has%20been%20the%20default%20style%20throughout%20Western%20history%5Cu2014see%20Alexander%20the%20Great%26%23039%3Bs%20beardless%20face%2C%20for%20example%2C%20as%20the%20Greek%20heroic%20ideal.%20But%20the%20primacy%20of%20razors%20has%20been%20challenged%20over%20the%20years%20by%20four%20great%20bearded%20movements%2C%20beginning%20with%20Hadrian%20in%20the%20second%20century%20and%20stretching%20to%20today%26%23039%3Bs%20bristled%20resurgence.%20The%20clean-shaven%20face%20today%2C%20Oldstone-Moore%20says%2C%20has%20come%20to%20signify%20a%20virtuous%20and%20sociable%20man%2C%20whereas%20the%20beard%20marks%20someone%20as%20self-reliant%20and%20unconventional.%20History%2C%20then%2C%20has%20established%20specific%20meanings%20for%20facial%20hair%2C%20which%20both%20inspire%20and%20constrain%20a%20man%26%23039%3Bs%20choices%20in%20how%20he%20presents%20himself%20to%20the%20world.%20%20This%20fascinating%20and%20erudite%20history%20of%20facial%20hair%20cracks%20the%20masculine%20hair%20code%2C%20shedding%20light%20on%20the%20choices%20men%20make%20as%20they%20shape%20the%20hair%20on%20their%20faces.%20Oldstone-Moore%20adeptly%20lays%20to%20rest%20common%20misperceptions%20about%20beards%20and%20vividly%20illustrates%20the%20connection%20between%20grooming%2C%20identity%2C%20culture%2C%20and%20masculinity.%20To%20a%20surprising%20degree%2C%20we%20find%2C%20the%20history%20of%20men%20is%20written%20on%20their%20faces.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222024-05-31%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%229780226284149%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A42%3A23Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22Q8P2HL6T%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22McBride%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222025-06-03%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BMcBride%20SG.%20Whiskerology%3A%20The%20Culture%20of%20Hair%20in%20Nineteenth-Century%20America.%20Harvard%20University%20Press%3B%202025.%20264%20p.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Whiskerology%3A%20The%20Culture%20of%20Hair%20in%20Nineteenth-Century%20America%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sarah%20Gold%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22McBride%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22A%20surprising%20history%20of%20human%20hair%20in%20nineteenth-century%20America%2C%20where%20length%2C%20texture%2C%20color%2C%20and%20coiffure%20became%20powerful%20indicators%20of%20race%2C%20gender%2C%20and%20national%20belonging.Hair%20is%20always%20and%20everywhere%20freighted%20with%20meaning.%20In%20nineteenth-century%20America%2C%20however%2C%20hair%20took%20on%20decisive%20new%20significance%20as%20the%20young%20nation%20wrestled%20with%20its%20identity.%20During%20the%20colonial%20period%2C%20hair%20was%20usually%20seen%20as%20bodily%20discharge%2C%20even%20%5Cu201cexcrement.%5Cu201d%20But%20as%20Sarah%20Gold%20McBride%20shows%2C%20hair%20gradually%20came%20to%20be%20understood%20as%20an%20integral%20part%20of%20the%20body%2C%20capable%20of%20exposing%20truths%20about%20the%20individuals%20from%20whom%20it%20grew%5Cu2014even%20truths%20they%20wanted%20to%20hide.As%20the%20United%20States%20diversified%5Cu2014intensifying%20divisions%20over%20race%2C%20class%2C%20citizenship%20status%2C%20and%20region%5Cu2014Americans%20sought%20to%20understand%20and%20classify%20one%20another%20through%20the%20revelatory%20power%20of%20hair%3A%20its%20color%2C%20texture%2C%20length%2C%20even%20the%20shape%20of%20a%20single%20strand.%20While%20hair%20styling%20had%20long%20offered%20clues%20about%20one%5Cu2019s%20social%20status%2C%20the%20biological%20properties%20of%20hair%20itself%20gradually%20came%20to%20be%20seen%20as%20a%20scientific%20tell%3A%20a%20reliable%20indicator%20of%20whether%20a%20person%20was%20a%20man%20or%20a%20woman%3B%20Black%2C%20white%2C%20Indigenous%2C%20or%20Asian%3B%20Christian%20or%20heathen%3B%20healthy%20or%20diseased.%20Hair%20was%20even%20thought%20to%20illuminate%20aspects%20of%20personality%5Cu2014whether%20one%20was%20courageous%2C%20ambitious%2C%20or%20perhaps%20criminally%20inclined.%20Yet%20if%20hair%20was%20a%20teller%20of%20truths%2C%20it%20was%20also%20readily%20turned%20to%20purposes%20of%20deception%20in%20ways%20that%20alarmed%20some%20and%20empowered%20others.%20Indeed%2C%20hair%20helped%20many%20Americans%20to%20fashion%20statements%20about%20political%20belonging%2C%20to%20engage%20in%20racial%20or%20gender%20passing%2C%20and%20to%20reinvent%20themselves%20in%20new%20cities.A%20history%20inscribed%20in%20bangs%2C%20curls%2C%20and%20chops%2C%20Whiskerology%20illuminates%20a%20period%20in%20American%20history%20when%20hair%20indexed%20belonging%20in%20some%20ways%20that%20may%20seem%20strange%5Cu2014but%20in%20other%20ways%20all%20too%20familiar%5Cu2014today.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222025-06-03%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%229780674300668%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A31%3A01Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22IFGM6HRS%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A11711645%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Khalifa%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222025-07-01%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bclear%3A%20left%3B%20%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-left-margin%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bfloat%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B1.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-right-inline%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bmargin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3BKhalifa%20AA.%20Bearded%20surgeons%3A%20Friend%20or%20foe%20in%20the%20fight%20against%20surgical%20site%20infections%3F%20An%20updated%20and%20comprehensive%20literature%20review.%20J%20Musculoskelet%20Surg%20Res.%202025%20July%201%3B9%283%29%3A310%26%23x2013%3B6.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Bearded%20surgeons%3A%20Friend%20or%20foe%20in%20the%20fight%20against%20surgical%20site%20infections%3F%20An%20updated%20and%20comprehensive%20literature%20review%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ahmed%20A.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Khalifa%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22One%20of%20the%20significant%20complications%20occurring%20after%20various%20surgical%20procedures%2C%20including%20orthopedics%20and%20traumatology%2C%20is%20surgical%20site%20infection%20%28SSI%29%2C%20which%20poses%20an%20incidence%20of%20up%20to%203%25%20and%20might%20lead%20to%20an%20increase%20in%20hospital%20stays%2C%20with%20a%20further%20increase%20in%20the%20economic%20burden%20on%20the%20healthcare%20system.%20Factors%20contributing%20to%20the%20SSI%20occurrence%20could%20be%20divided%20broadly%20into%20factors%20related%20to%20the%20patient%20%28endogenous%29%20or%20those%20associated%20with%20the%20surgical%20procedure%20%28exogenous%29%2C%20which%20include%2C%20in%20part%2C%20the%20behavior%20and%20attitude%20of%20healthcare%20personnel%20and%20operative%20theater%20staff%20members%2C%20including%20surgeons.%20Facial%20hair%20and%20its%20correlation%20with%20increased%20bacterial%20contamination%20and%20colonization%20have%20been%20an%20issue%20of%20investigation.%20Furthermore%2C%20the%20relationship%20between%20healthcare%20personnel%5Cu2019s%20facial%20hair%20%28mainly%20beards%29%20and%20the%20incidence%20of%20SSI%20was%20also%20evaluated.%20In%20this%20comprehensive%20narrative%20review%2C%20we%20aim%20to%20discuss%20the%20literature%20evidence%20related%20to%20facial%20hair%20and%20its%20correlation%20with%20SSIs.%20Studies%20showed%20conflicting%20results%20regarding%20the%20increase%20in%20bacterial%20contamination%20related%20to%20keeping%20facial%20hair%20compared%20with%20being%20clean-shaven.%20However%2C%20the%20correlation%20between%20having%20facial%20hair%20and%20increased%20SSI%20incidence%20was%20disputed.%20Healthcare%20personnel%20are%20encouraged%20to%20stick%20to%20covering%20their%20heads%20and%20facial%20hair%20while%20participating%20in%20patient%20care%20activities%2C%20especially%20inside%20the%20operative%20theaters%2C%20as%20this%20has%20been%20shown%20to%20decrease%20the%20rates%20of%20bacterial%20shedding%20from%20those%20having%20facial%20hair%2C%20even%20with%20long%20beards.%20Furthermore%2C%20surgeons%20should%20not%20be%20asked%20to%20shave%20their%20beards%20for%20the%20sake%20of%20protecting%20their%20patients%20from%20a%20possible%20increased%20SSI%20risk%3B%20instead%2C%20they%20should%20be%20encouraged%20to%20cover%20their%20beards%20and%20practice%20proper%20face%20hygiene.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222025-07-01%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.25259%5C%2FJMSR_148_2025%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%222589-1219%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22JCTK4HGA%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-08-07T16%3A23%3A12Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D 1.

Beard Oil Market Size, Share & Growth Analysis Report 2030.

1.

Penn State Health, Mid Penn Bank raise $340,000 during ninth ‘No Shave November’ | Penn State University.

1.

Creer E. A Popular Treatise on the Human Hair: Its Management, Improvement, Presentation, Restoration and the Causes of Its Decay, with Some Observations on the Use of Powders, Face Paints, Cosmetics, and Hairdyes. The author; 1865. 104 p.

1.

Parisi AV, Turnbull DJ, Downs N, Smith D. Dosimetric investigation of the solar erythemal UV radiation protection provided by beards and moustaches. Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 2012 July 1;150(3):278–82.

1.

Rana M, Qin DB, Vital-Gonzalez C. Mistaken Identities: The Media and Parental Ethno-Religious Socialization in a Midwestern Sikh Community. Religions. 2019 Oct 12;10(10):571.

1.

Withey A. Concerning Beards: Facial Hair, Health and Practice in England 1650-1900. Bloomsbury Academic; 2021. 343 p.

1.

El Edelbi M, Hassanieh J, Malaeb N, Abou Fayad A, Jaafar RF, Sleiman A, et al. Facial microbial flora in bearded versus nonbearded men in the operating room setting: A single-center cross-sectional STROBE-compliant observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Oct 7;101(40):e29565.

1.

Brewer G, Singh J, Lyons M. The Lived Experience of Racism in the Sikh Community. J Interpers Violence. 2023 Dec 7;39(11–12):2415–36.

1.

Oldstone-Moore C. Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair. University of Chicago Press; 2024. 347 p.

1.

McBride SG. Whiskerology: The Culture of Hair in Nineteenth-Century America. Harvard University Press; 2025. 264 p.

1.

Khalifa AA. Bearded surgeons: Friend or foe in the fight against surgical site infections? An updated and comprehensive literature review. J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2025 July 1;9(3):310–6.